Australia’s Price for Punishment

Australia is continuing to invest in juvenile detention centres, despite gruelling evidence that it does more harm than good.

A growing trend of over-policing and over-jailing is overflowing juvenile detention centres, with rampant human right violations occurring behind bars.

Harrowing investigations into juvenile detention centres have found several instances of human rights violations, including the use of unnecessary force and prolonged isolation – with some children being held in their cells for up to 23 hours per day.

And yet Australia is continuing to invest in detention, and the most vulnerable members of the community are paying the price.

Dr Thalia Anthony, Professor of Law at the University of Technology Sydney is a prominent voice in the discussions surrounding Australia’s criminal justice system.

She advocates for the “de-carceration” and re-evaluation of punitive practices.

According to her, the penal system does more harm than good, and only continues the cycle of trauma, addiction, unemployment, homelessness, and further imprisonment.

“We have seen for almost 250 years that [incarceration] doesn't work and yet we keep reproducing the same mistake,” Dr Anthony says.

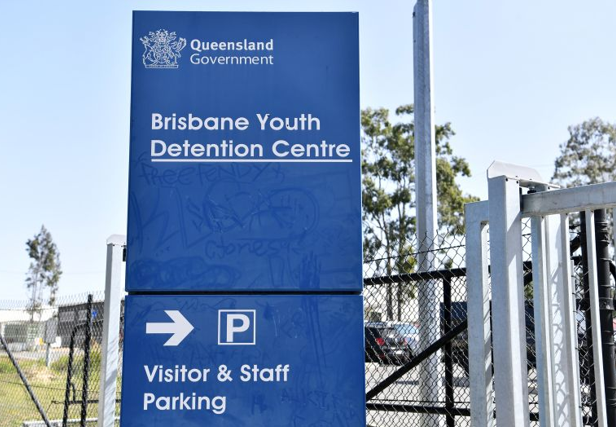

Queensland, Australia’s largest state for prison populations, has invested $250 million to build a new youth remand facility in Brisbane.

This follows the controversial introduction of policies by the Queensland Government which have overridden the state’s Human Rights Act.

In February, juvenile detention centres saw a boom in numbers after Queensland overrode the amendment, enabling children who breach bail conditions to be charged with a criminal offence.

The overflowing numbers led Queensland to override the amendment again in August to hold youths in adult watchhouses.

A discussion surrounding incarceration would be incomplete without acknowledging that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are the most incarcerated groups in the world – comprising 32 percent of adult detention populations and 60 percent of juveniles detention populations, while barely making up 4 percent of the national population, according to the latest figures from the Institute of Health and Welfare.

“What the penal system does is complete that disempowerment,” Dr Anthony says.

“Because when First Nations people are either policed, put in police cells, put in prisons or youth detention, they not only lose that sense of connection to family or to country, but they also … undergo a form of social death.”

“They lose control over their capacity to engage in society, their capacity to live as a First Nations person with dignity, and even capacity over one's body.”

“And its ultimate manifestation involves deaths in custody,” Dr Anthony says.

Despite these challenges, organisations like the Justice Reform Initiative are advocating for a comprehensive overhaul of the Australian Justice System.

“A lot of our advocacy is really trying to push the government to redirect that funding and give self-determination back to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities – to the solutions that they know will work for their community,” Ms Kerr says.

In an effort to address these disparities, the Australian Government has unveiled the “largest commitment to justice reinvestment ever delivered by the Commonwealth.”

The “historic $99 million First Nations Justice package” aims to support First Nations communities in determining local solutions and “divert at-risk youth and adults away from the criminal justice system,” a spokesperson for the Attorney General said in a statement.

“It’s about community-led and holistic approaches to improve peoples’ lives, and strengthen community safety.”

Although a proactive step, this historic package pales in comparison to the millions spent on detention-based services.

“The problem … is that so much money is being poured into building new prisons and locking people up as the default response,” JRI’s Aysha Kerr says.

Despite new facilities and policies aimed at cracking down on youth crime, Ms Kerr believes this is doing little to solve problems long-term.

“The current system of sending people to prison does not work.”

“This is resulting in young people being remanded, going into prison, being let out of prison, and then all of the … circumstances in their life that are leading them to engage in that behaviour still exist,” Ms Kerr says.

Ms Kerr says that more resources should instead be invested in “community-led and culturally modelled alternatives to prison.”

One such example is Red Dust Healing. A First Nations-led organisation which aims to empower individuals and divert them away from the criminal justice system.

“It’s about restoration of people and giving individuals some tools to help them understand how lives work,” explains Red Dust Healing founder Tom Powell, a Warramunga man.

Mr Powell continued, sharing his strategy to create genuine change in his community.

“Empowering the individual, empowering the families, empowering the households and empowering communities to be part of their own solution. That’s what Red Dust does,” he said.

Red Dust Healing utilises holistic educational tools to help people understand and navigate external pressures, like rejection.

“What makes Red Dust, unique – I will not say better, but unique – from other programs is that it deals with the underlying factor of rejection: abuse, neglect, abandonment, domestic violence. But grief and loss is a huge part of rejection.

“And if the rejection is not delt with … nothing much changes,” Mr Powell says.

After working in the Department of Juvenile Justice for over a decade, Mr Powell noticed rejection didn’t stop and start with the individual.

“I believe that if problems lie in communities, so too do the answers.”

He found “that a lot of rejection was just repeating the things that have happened in our own lives.”

His experiences working with youth helped him realise that, to create genuine change, he needed to “help the whole family.”

And so far, he has. Since Red Dust Healing’s genesis, over 15,000 people have gone through the programs, with only 11 having not finished.

Data shows that programs focused on prevention, diversion, and early intervention do much more to rehabilitate and redirect people away from the criminal justice system and recidivism.

When individuals are locked behind bars, they are exposed to further harm and trauma – furthering resentment, anger, and pain, which then flows into the communities.

This is even more damaging with juveniles, who have not yet fully mentally and emotionally developed.

And yet, Australia continues to ignore the calls of human rights groups to stop locking up kids, and instead, invests millions of dollars into more detention-based services.

More funding needs to be directed away from these facilities and into community-led diversion programs, which we know do much more to reduce harm for individuals and the public.

Post a comment