Caught in a Cycle of Crime

30 October 2024

Almost half of all discharged prisoners spend their first night homeless

It’s a grim reflection of Australia’s current attitudes towards criminal behaviour and its reliance on punishment over rehabilitation.

Once someone completes their court-mandated sentence, they are free to rejoin society once again. But if they aren’t provided adequate reintegration support, this often results in homelessness and a return to destructive habits, crime, and custody.

Here lies the cycle.

It drives people deeper into isolation and destitution; ultimately harming the community by creating more victims, unsafe neighbourhoods, and rising costs for taxpayers who fund temporary fixes.

Criminologists, charities, and academics say it is much cheaper, and more effective, to divert spending towards alternatives like rehabilitation, reintegration, and crime prevention.

This allows caseworkers to individually analyse offenders and cater support programs to reduce the chance of re-offending, ensuring a safer community for all.

Inside, prisoners may participate in various rehabilitative programs designed to prepare them for release – employability training, psychological evaluations, and the like.

But while these vital avenues of reintegration do exist – in theory – they often get lost amid overcrowded and understaffed facilities.

And so, once someone completes their sentence, they simply return to the life they know. They’re given the clothes they were wearing on the day of their arrival, a small amount of money, and an Uber voucher if they’re lucky – and that’s it.

I have witnessed it time and time again while volunteering with a Brisbane homeless support charity, Northwest Community Group.

Every week, I’ll meet people who have been released from custody that day, and they’ll come to us for a tent, sleeping bag, and a number of other essentials.

They have nothing and no one once they get out.

I fear this reality often comes with a sense of apathy towards prisoners – both socially and from institutions – that whatever despair they experience is simply part of their punishment.

And I do agree that certain people waive their right to be members of our society when they commit particularly heinous crimes. As the fundamental aim of prisons, it is vital that violent and dangerous criminals are isolated from community, to make everybody feel safe.

But when we hear a statistic like, ‘Almost half of all discharged prisoners spend their first night homeless,’ we aren’t just talking about our most vicious. It’s people from a range of crimes and backgrounds. And they deserve the chance to rejoin society.

Though the stigma attached to these people makes it extraordinarily hard to do so.

Discrimination limits their chances of applying for a house, getting a job, and becoming active members of our community. It hinders their ability to get better, and when all else fails, they are pushed towards homelessness and crime.

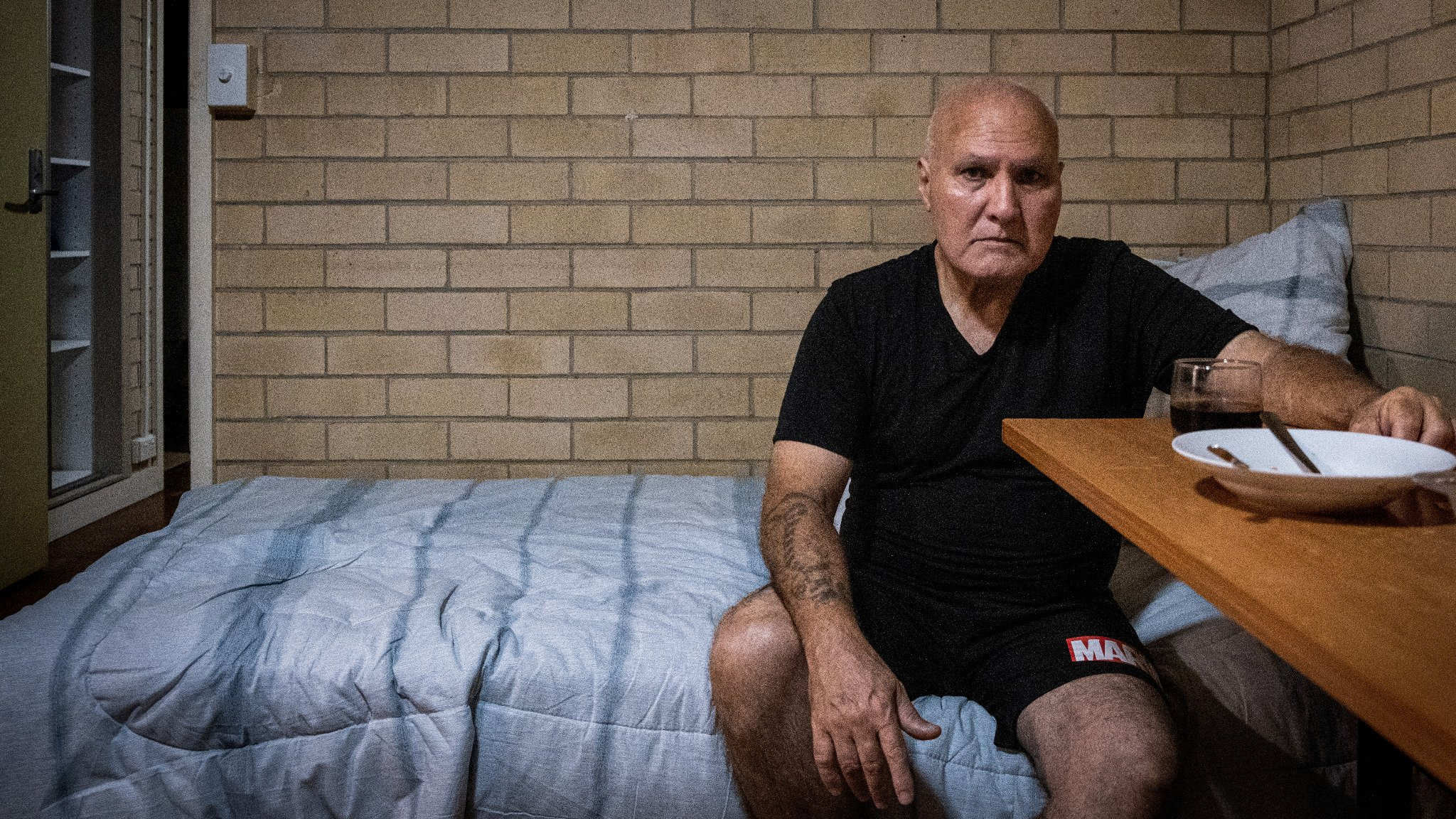

Donald

“I'm not proud of my criminal record, but I lost track of how

many times in and out, in and out – all the time.”

Donald Green explained to me how easy it is to get caught in the cycle of homelessness and crime after release.

After spending most of his life behind bars, he never felt as if he was properly supported for release, falling each time back into homelessness and the same destructive habits that come with it.

The last stint was different, however.

After enduring an excruciating wait on Brisbane’s broken housing list, I was invited to Donald’s unit with the founder of Northwest Community Group, Paul Slater.

We sat down on his bed – the only piece of furniture in an otherwise empty home – and he told us his life story.

Born in Papua New Guinea, Donald and his family came to Brisbane at the age of 13. With little savings, they ended up sleeping under the Story Bridge.

Donald talked of the difficulty escaping labels. How people would often call him a “disgusting person,” just for the way he was living.

This perpetual stigmatisation of poverty and youth homelessness can keep people trapped for life.

“It’s hard to try to get your life on track yourself because ... you’re not able to turn around and fit within the society,” he explained.

Kids who grow up around domestic violence, mental health issues, or financial stress may often spend more time away from their families and move into higher-risk environments.

As a self-described hard-headed kid, Donald and the ‘Valley Street Boys’ found sanctuary amongst the Kangaroo Point cliffs and would go out and steal what they could to survive.

Oftentimes, this led to run-ins with the law.

Desperado Decades

The cycle caught Donald from an early age. A series of poor choices made out of desperation led him to juvie at the notorious Westbrook Training Centre.

It could have offered a chance for improvement. But that didn’t happen.

Here, along with many other young boys, Donald faced constant abuse by the staff and was ripped of his adolescence and education.

Citing an inability to be controlled, he was moved to Boggo Road Gaol at the age of 16.

From getting beaten by guards to spending days confined in “the black hole,” Donald lived the horror stories of Boggo Road for years.

The harsh conditions left little room for rehabilitation; instead, itonly reinforced anti-social behaviour.

Yet, amid the brutality, Donald was able to forge a community alongside like-minded inmates.

“Everyone respected one another, regardless of what crimes you did. You had all the ... groups coming together to build networks for that person living in dire straits,” Donald said.

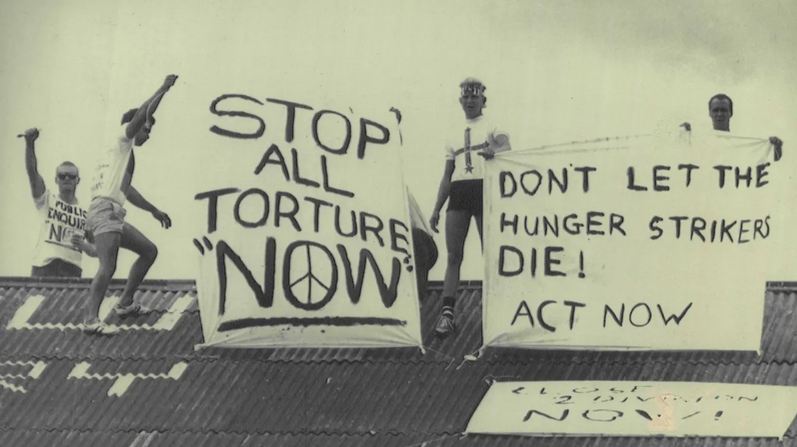

Together, they founded a union to give prisoners a collective voice to call out abuse and challenge the correctional services in court.

“We were trying to change the whole system,” he said.

For over a decade, riots, hunger strikes, murders, and escapes were frequent at Boggo Road, as prisoners demanded an end to the injustice.

It had culminated in the iconic rooftop protests of the 1980s – a symbolic display of resistance from the prisoner rights movement during that decade. A cause Donald helped lead.

“That was the last straw,” Donald asserted. “We were to get our message across the world.

“We need to be treated like a human being. We need to get people to realise that no matter how long you do inside of these places, sooner or later, them doors are going to open back up for us.

“If we have not got any family support or community support ... then we turn back to our lifestyle – crime, drugs, and whatever else.”

Their demonstrations gained massive support from the public and shone a spotlight on the systemic human rights abuses that infested the prison yard, ultimately leading to a royal inquiry.

The report recommended extensive and sweeping reforms; a “complete cultural change” from punishment and retribution to correction and rehabilitation.

A new era?

Today, Australian prisons offer various programs to help rehabilitate and reintegrate prisoners once they get released.

But there is still a long way to go.

Since the new millennium, prison populations have doubled, and facilities are struggling to find enough staff to match.

I spoke to a former employee of Queensland Correctional Service who’s worried that this instability plays a massive role in the cycle.

They said a lack of staff meant prisoners miss out on crucial, regular appointments with psychologists, trainees, and parole and probation officers.

A key part of the modern reforms prisons tout is individualised care – developing a structure for rehabilitation and release on a case-by-case basis. It’s something that is included in every program and policy of correctional centres.

But when there aren’t enough employees, prisoners don’t receive this care and face a much greater challenge when reintegrating back into society.

Increased funding is one solution.

Currently, state and federal governments are pouring $6.4 billion annually into the construction and operation of new prisons, costing taxpayers upwards of $150,000 per prisoner per year, according to the Institute of Public Affairs.

This should cover the costs to ensure individuals are treated appropriately, but again, it would be even cheaper and more effective to allocate funds towards alternative pathways.

While there is no single solution, providing stable housing has been shown to drastically reduce recidivism.

Public and private organisations have made significant progress in supporting prisoners transitioning out of custody by providing bond and rental assistance, as well as increasing funding for social housing and specialised homelessness services.

Initiatives like these, partnered with external organisations to help foster community connection, is a great way to break the cycle.

Melbourne-based organisation Vacro has helped thousands of families through careful pre- and post-release support. They focus on destigmatising and reconnecting prisoners to community and family to ensure they rejoin society and divert from their destructive paths.

As many exiting prison may not have family support structures in place, exposure to external orgs like Vacro can mean the difference between a successful release and an unsuccessful release.

But many continue to fall through the cracks and land on the streets.

When Boggo Road shut down, Donald went through a number of other prisons.

Each time getting released, trying to figure out an alternative route to survive with the little resources he had, and each time falling back into crime.

So it goes.

Donald’s final stint ended in 2023.

“They just kicked me out of the jail ... gave me $400 crisis money and they said, ‘See you later, sign on the dotted line’,” he recalled.

“That was it. I went straight from there onto the streets in

Brisbane.”

With only the clothes on his back, less than a week’s rent, and no connections to family, employment, or housing, Donald was primed to continue the cycle once more.

It’s during these periods where former inmates are at their most vulnerable.

Dr Thalia Anthony, a Professor of Law at Sydney’s University of Technology, researched the prevalence of ‘hyper-policing’ and found that people experiencing homelessness are

disproportionately criminalised.

She says constant police surveillance, harassment, and apprehension of people sleeping rough drive them along the conveyor belt from the streets “into the panopticon of prisons.”

“This is very cyclical,” Dr Anthony explained. “You put people on the streets, you over police them, you put them in prison, which means they're back on the streets.

“There's no way to provide a circuit breaker without the willingness of government to say, ‘Well, we're going to rethink law enforcement.’”

A large part of Dr Anthony’s work and advocacy centres around the idea of ‘de-carceration’ – moving away from punishment and towards rehabilitation and community alternatives.

The Netherlands is a shining example of this movement. Between 2005 and 2016, they saw prison populations plummet by nearly half, with categories of crime consistently falling below 50%.

With such low prison populations, funding can be allocated back into the community, with empty cell blocks being transformed into hotels and community centres.

While Australia’s prison population continues to grow, Dr Anthony is worried that the option of community reintegration becomes further and further out of reach.

“Ideally, you want a system that gives [prisoners] lots of opportunities that help them heal from whatever substance abuse or trauma they may have suffered, and then that creates a pipeline,” she said.

“If they start a job inside, you'd hope that ... there is an organisation also providing something similar on the outside.

“But when you're just racking and stacking people, that's all compromised, because people just have to stay in cells because they can't be supervised.”

Even with successful program engagement, support rarely continues upon release. So, once you hit the streets, it’s up to sheer determination to get better.

This time, Donald vowed he would break the cycle.

“When you get to 61, you put the brakes on and go ‘Woah, this is enough’. I don't want to be a name, number, statistic and be another black death in custody,” he said.

He pitched up his tent alongside others by the Brisbane River and joined a community of people facing similar struggles.

He took it upon himself to maintain a safe, clean space for everyone, working hard to keep the area orderly and prevent it from becoming a hotspot for drug activity.

Donald said it wasn’t typically the locals who made it this way, but rather “undesirables” who “came out of the woodworks”.

“We were trying our hardest to keep under wraps or under control by making sure there were no needles, and that was a challenge within itself,” Donald said.

This was his way of avoiding problems with the council and rejecting social stigma.

“We may be homeless, but we are not animals,” he said.

His goal was simple yet challenging: to create a peaceful place for everyone, and live with a sense of comfort and dignity.

Paul Slater met Donald not long after he arrived at the river as a part of his nightly route delivering essentials and connecting people with other services.

“He was a really lovely guy,” Paul said. “He would spend most of his time telling me about all the things he was doing to help other people. That’s just the way he functioned.”

These attitudes are rare enough to really stand out, and allow charity workers, like Paul, to provide much-needed support more effectively.

“When he realised what I do there, he would message me and say such and such needs this and that. So, it's actually really handy to have someone on the ground … and make sure that I have maximum impact out there.”

For many, this community-driven spirit is crucial. Charities like Northwest Community Group often become the last lifeline for people in need, stepping in as government agencies struggle to keep up with the increasing demand for housing and support services.

More than 45,000 people are currently registered on Queensland’s housing waitlist, with half being actively homeless.

And yet, after years of calling cells and streets his home, Donald finally secured housing.

It was a small one-bedroom unit in a dodgy housing complex, but it was the first time Donald had a proper place to live.

Generally, once this process is completed and you’ve been handed the keys to your social housing, agencies are expected to visit periodically and ensure a supported transition.

For someone like Donald, who has been institutionalised for most of his life, it’s challenging to come back into a changing world and learn how to navigate it.

“I don’t know where to go or what to do,” he lamented.

From simple challenges like getting a public transport card, and linking up with community groups, to securing appointments with doctors, Donald struggled to acclimate in his new environment.

“My main goal was to come to a place that I could call home for the rest of my life.

“But I feel that I've been left here to defend for myself. Left to try and survive the best way I see fit.”

Months passed with Donald waiting and making phone calls before any agencies finally visited his new home.

In the meantime, Paul and Bronwyn Wood stepped in.

After visiting Donald as a Northwest Community Group volunteer, Bronwyn recognised a need to be filled and soon founded Next Step Connect, an organisation that connects newly housed individuals with resources, services, household items, and community support.

“I think it made a difference having some normality in Donald’s life,” Bronwyn said. “Even from day one, he couldn't believe that people would help him. He’d ask, ‘Why are you helping?’”

Thinking back to the first few months, Bronwyn was stunned at how the prison had dumped him with no connection to the outside world.

“Oh, my God,” she exclaimed. “How can Donald be released?

“Clearly the prisons know his glasses are broken. He has no teeth. He says he can't hear very well. He’s clearly got health issues and mental health issues. He's got a house with hardly anything in it.

“They've just thrown them into this community – and that's a rough community. You could feel the environment is not safe,” Bronwyn said.

Donald recounted how, for weeks, strangers would knock on his door offering drugs. His neighbours were fellow former inmates and bikies, and the constant presence of violence and police call-outs loomed over him.

“I hate this place,” Donald confessed.

“It's so violent and I can feel myself getting violent. I feel

like I'm gonna do something.”

Donald wanted so badly to reform and reconnect with his family, but the cycle seemed to be repeating.

Donald’s isolation often made him want to return to the streets, where he was part of a familiar community and could access food, laundry services, and medical support.

"How can you survive in these places if people are not going to take you through a system where you are able to live reasonably and comfortably and are able to support yourself?” Donald argued.

“And when you're not to that point … why should we be left alone?”

He emphasised the need for agencies to refocus their efforts on assisting individuals in securing employment and rebuilding relationships with family and community.

“We need to be treated as a human being … not left and dumped in a place to defend for yourself. Where you’re a nobody. Just a name, number, statistic.

“Someone will end up coming and doing a welfare check and find us dead.”

Legacy

On August 9, 2024, Donald was found dead in his apartment bypolice during a welfare check.

He was murdered.

A week earlier, a call was made about an altercation that had occurred at Donald’s place. But nothing came from it.

“I’m so upset that someone thought they had the right to take Donald away from us,” Paul said in a Facebook memorial.

“He hadn’t finished his full life story yet, and that has been robbed from him.”

Donald is just one of many caught in a cycle that begins and ends in despair.

Yet within this cycle, Donald left behind a powerful legacy.

He navigated a broken, discriminatory, and abusive system; doing the best he could to survive.

Through his prisoners' union, he fostered a collective voice and established support networks for those re-entering society.

His protests at Boggo Road catalysed its closure and led to sweeping reforms in Australia’s prison system.

He inspired Bronwyn to found Next Step Connect, to help individuals settle into their new homes and find pathways toward community and reintegration.

Ultimately, Donald wanted to live quietly in his new home, helping others where he could, and reconnect with his family.

His tragic story serves as a reminder of the individuals who are caught in these cycles. It’s proof of the urgent need for reform in our approach to rehabilitation.

Without it, communities will continue to suffer from the perpetual struggle of homelessness and recidivism — struggles that can be alleviated.

Experts and those with lived experiences tell us that a drastic redesign of our justice system is needed. One centred around individuals and their needs, and supported by external organisations to improve connections with housing, employment, family and community.

But it’s not just institutions. As a society, we need to understand how stigma traps people. The inability to push past labels and history prevent people from changing. Talk with local organisations and the people they support.

This cycle has an end, let’s get there together.

Post a comment